This essay addresses democracy and the meaning and importance of public support. The entire essay was posted on December 9, 2021 in Between Hell and High Water. The author, Michael Koetting, writes a regular column, Between Hell and High Water, and is an advisor to Civic Way. Michael holds a PhD in Sociology from Harvard and served as VP of Planning at the University of Chicago Medical Center and Deputy Director for Planning at the Illinois Department of Health and Family Services, among other public sector positions. Michael also created and taught “American Democracy and You” in the Honors College at the University of Illinois-Chicago.The Basics of Supporting Democracy

Democracy needs two things to be sustained: deep popular support for the idea of democracy and an appropriate governing vehicle to make it work. Today’s post considers the status of popular support for democracy in America.

By support for the idea of democracy, I mean something that’s both simple and complicated. It starts with some understanding that democracy is inherently imperfect. Since it is fundamentally a system for mediating a series of compromises among different values and solutions, there will always be plenty of reasons to be unhappy.

Supporting democracy, then, is simply accepting that your side doesn’t always win and that you will, more or less happily, go along with the majority—even if that means accepting some limits on your individual preferences from time to time.

Accepting Election Results

It’s not like there is a neat prescription as to what this means in practice. There aren’t many direct ways people are called upon to indicate their support for democratic principles. Voting is a basic minimum, but no more than that. There is voting in any number of decidedly illiberal countries and, in any event, it is something many people do without much thought about the underlying principles.

That said, even at this most basic level, there is reason to be concerned about our commitment to voting principles. One obvious issue is the reluctance of a large section of the electorate to accept the results of the 2020 election.

I suspect there is no easy answer as to what people mean when they say the election wasn’t “legitimate.” Some probably think there were actual miscounts or other forms of outright fraud. Some think that too many people voted who should have been prohibited from voting or whose ballots should have been rejected over a technicality, but weren’t, in a way that unfairly favored Democrats.

And some may have felt that voting should be hard and making it easier allowed “too many” minorities to vote. Whatever. The important thing is that so many Americans were willing to tell a pollster they didn’t think the election results were legitimate.

This suggests a serious weakening in the communal acceptance of election results.

Accepting Election Results as Partisan

By way of comparison, in 2000, one-third of Democratic voters believed Bush “stole the election.” In 2016, 25 percent of Democratic voters believed Trump’s election was illegitimate. And in both those elections, the Democratic candidate won by the popular vote by a reasonable margin.

In contrast, about two-thirds of Republicans see the 2020 election results as illegitimate, even though Trump lost the popular vote by a significant margin in an election which all neutral observers have declared one of the most fraud free elections in recent time.

On top of this, we have the entirely unprecedented circus of a presidential candidate refusing to concede and stoking up one entire political party into a constant refrain that the election was illegitimate and that it should be overturned. It has also spawned a spate of attempts by Republicans to make voting more restrictive or easier to overturn actual results.

Voting — Right or Privilege?

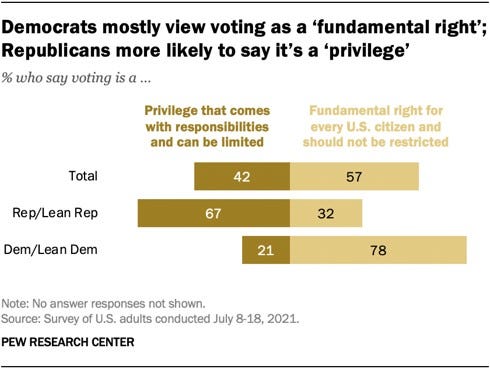

In this environment, it is little surprise that many people question voting as a “fundamental right”. The idea that voting should be a contingent rather than fundamental right suggests an erosion in the acceptance of a broad-base democracy, something the Constitution offers as a fundamental right.

American tolerance of voting as a fundamental right has always been less than universal—particularly with regard to people of color—but these are sufficiently alarming numbers as to wonder who these people think are part of “democracy.”

Democracy and Public Trust

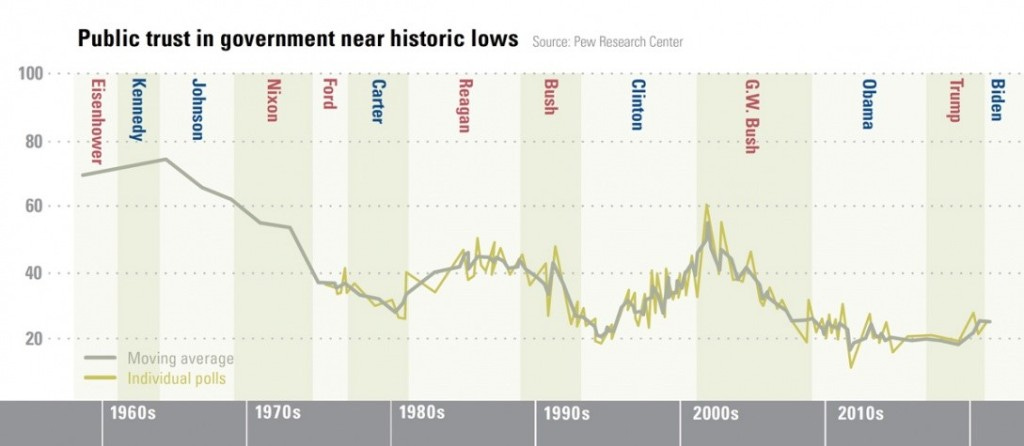

One measure of the degree of support enjoyed by a particular form of government is to ask people how much they trust government to do the right thing. This is not quite a direct evaluation of democracy per se, but it provides an important yard stick of how much people value the current form of government. The Pew Foundation has been studying this issue for years and the results are worrisome.

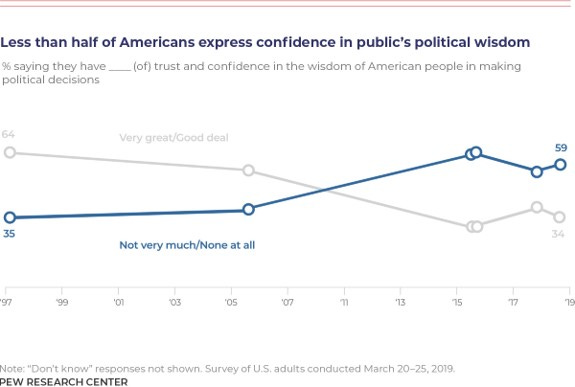

A related measure is trust in “public political wisdom”. Pew has also been tracking this, but for a much shorter period. Still, this is another trend unhealthy for democracy.

There is an abundance of recent surveys specifically suggesting concern about the status of our democracy. To take only two:

A PBS poll this summer suggested that two out three Americans think our democracy is seriously threatened.

An AP/NORC poll shows only 16% of Americans think our democracy is working well, although another 38% say it’s working somewhat well.

Perhaps even more troubling, a Harvard Institute of Government survey of young people (18-29), shows more than half this group believes the US is either a “failed democracy” or “a democracy in trouble”, with Republicans having a decidedly more pessimistic view.

This survey also found that only 57% of this population felt it was “very important” that we had a democracy; 7% said it was “not very” or “not at all” important. But these are all point-in-time surveys. Maybe Americans have always thought our democracy was threatened.

Yascha Mounk and Roberto Stefan Foa have data covering the last 25 years that show a steady deterioration in popular satisfaction with democracy in the US. In their survey, now more than half of Americans indicate they are dissatisfied with our democracy, a result consistent with the above-cited surveys on the topic. As they say in interpreting this and data on other countries, citizens have become steadily disenchanted with their democratic systems.

As a result, they are more and more willing to vote for extremist politicians who promise to break with the status quo.

Democracy and the Middle Class

One of the strong sentiments of commentators for the last 100 years is that American democracy is supported by the existence of a strong middle class that feels itself appropriately served by the status quo. Not necessarily the economically richest, but not so far below that that they still feel an ownership stake in the country and not so worried about losing that status that they are overcome by fear.

As I suggested in my last post, for democracy to be sustained, a substantial portion of the population must be committed to the idea of democracy. I don’t believe that group can maintain crucial mass unless there is a large middle class and some practical limits on the severity of class divergence.

Ganesh Sitaraman makes this same point in a book and a very important article in the Atlantic. Without a middle class, he says, the differences between groups become stark and the idea of compromise and adaptation that are essential to democracy start to erode. And there can be little argument that we are witnessing a serious erosion of the middle class.

While this might not seem like a huge change, it is not happening in isolation. Not only is the income of the middle class shrinking, the income of the top 20% of the population is growing in leaps and bounds making it much harder to maintain the sense of a shared society. The point is not simply about income distribution. It’s about whether the society creates a sense that it’s a shared country with a shared sense of the rules by which we play.

When I was a kid, I knew my family wasn’t rich. But we weren’t poor and the differences between me and my friends from rich families weren’t that large. Our lives overlapped in so many more ways than is currently the case.

An increasing intergenerational income rigidity, which is both cause and symptom of the current malaise, furthers the sense that, not only are you stuck where you are, but the system will work to maintain those differences. At some point, people’s sense of the unfairness of it starts to make it seem as if the ideals of American democracy are hollow and they are willing to throw them over for a sense of respect and power.

The Last Word

I have presented a hodge-podge of measures, but they are discouragingly consistent in their story of increasing concern about the level of popular support for our democracy.

For the actual last word, I return to Mounk and Foa:

It is perfectly possible that democracies will recover from their current crisis in the years to come. But every new data point makes it that much harder to deny that such a crisis exists.