America’s Healthcare System – Part 9

The Slapdash Deployment of US Healthcare Resources

This is the ninth essay in Civic Way’s series on the US healthcare sector. In this essay, we start outlining healthcare’s major flaws. The author, Bob Melville, is the founder of Civic Way, a nonprofit dedicated to good government, and a management consultant with over 45 years of experience improving public agencies.

Highlights:

America’s disorderly patchwork of healthcare resources is a big reason our healthcare costs are so high, and our health outcomes so poor

National shortages in healthcare resources—like hospitals, clinics and providers—are attributable to many factors, but they are as much a function of geography as any other factor

The geography of healthcare resources—their uneven distribution across states and communities—is a natural byproduct of underlying fundamental forces like economics and federalism

So long as our healthcare resources serve profits—instead of needs—we will continue to bear disheartening health outcomes at an exorbitant cost.

Introduction

Every year, Americans pay far more for healthcare than citizens of other developed nations. Given how much we spend, we should have far better health outcomes than our peers. Sadly, our outcomes are actually worse, and the gap between the US and our peers is worsening by the year.

There are many reasons for this. Too little prevention (and public health capacity). Uneven care access and quality. Fragmented healthcare resources. An ill-conceived healthcare financing (insurance) system. Profit-driven (instead of people-driven) innovation. Antiquated administrative systems. In this essay, we focus on the third causal factor—fragmented resources. In future essays, we will outline the other major causal factors, and some bold—and not so bold—ideas for fixing those flaws.

The Impact of Fragmented Healthcare

There are many things wrong with US healthcare, but its organizational incoherence may be its most pernicious defect. As a result of our transactional approach to healthcare investment, US healthcare resources are more fragmented than in other developed nations.

What does this mean for Americans? It means that some get great healthcare and others do not. It means that some have superb facilities and providers while others, like those living in small rural communities and poor inner-city neighborhoods, do not. It means that we have too few of the providers we need—like primary care professionals—and too many of the providers that only some can afford—like plastic surgeons.

The fragmentation and thoughtless deployment of healthcare resources is true for healthcare facilities and workers alike. Facilities like hospitals and clinics are deployed based more on economics than needs. Healthcare workers shortages in some disciplines are nationwide, but more acute in poor urban and small rural areas.

The Distribution of Healthcare Facilities

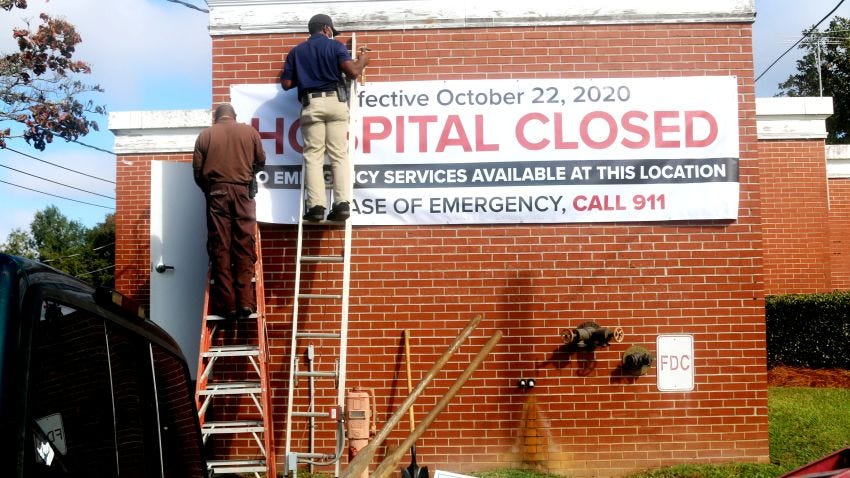

In urban areas, many hospitals—especially safety net hospitals[i]—are under siege. Most are financially distressed and, in recent years, some have experienced the same death spiral. Buy time by getting acquired or managed by a large chain. Cut lucrative specialties like obstetrics. Invest in renewal until the losses become unsustainable. Then, as cities like Chicago, DC and Philadelphia have witnessed, cease operations.

The hospital distribution problem may be even worse in rural communities. Many small rural hospitals have slashed services or closed (or both). Since 2005, at least 170 rural hospitals have closed[ii]. Today, nearly 30 percent of Texas’ counties have no hospital. Nationally, it is feared that another 20 percent of rural hospitals could be forced to close.

Hospitals aren’t the only unevenly distributed healthcare facilities. Primary care clinics and trauma centers suffer similar issues. Long-term care facilities, due in part to reimbursement and home health aide limits, are unable to survive in many areas. Pharmacies have abandoned over 600 rural communities[iii]. An estimated 40 million rural Americans live in pharmacy deserts[iv]. The shortage of mental health facilities, which most severely impacts rural and poor urban areas, worsened during the opioid epidemic.

The Dispersal of Healthcare Workers

While the distribution of healthcare workers is related to the placement of facilities, the correlation is not constant. In some cases, provider shortages and deployment imbalances occur somewhat independently of facility placement. This is true for many healthcare professionals, including primary care physicians and nurses.

Overall, the US has fewer physicians per capita than virtually every economic peer. According to the American Association of Medical Colleges, our national physician shortage—including general practitioners—could be 140,000 physicians by 2033. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, we need over 14,000 primary care physicians[v]. These deficiencies are most severe in regions like the Mississippi Delta.

There also is a national nursing shortage. According to the American Association of Colleges of Nursing, the US needs over 200,000 new nurses every year. By 2030, over one million new registered nurses may be needed. The National Association of School Nurses has reported that at least 25 percent of schools have no nurse. As with other healthcare workers, nursing shortages are serious in some areas than others.

Causal Factors for Healthcare Shortages

There are many factors that contribute to our country’s healthcare resource shortages as well as their uneven deployment. Some are noted below.

Regulatory barriers – Some states impose excessive restrictions on critically-needed services (e.g., primary care, mental health and substance use services).

Licensing hurdles – Many states have antiquated licensing restrictions that bar cost-effective alternatives (e.g., cross-state telemedicine or routine care by nurses and dental therapists).

Medical education – The US has the world’s most costly medical-education system for physicians and nurses[vi], and unduly limits class sizes and the number of enrollees.

Recruiting challenges – Compensation and working condition issues persist. Some healthcare workers won’t relocate to some areas regardless of incentives, some states impose unreasonable burdens on foreign-trained physicians and nurses[vii] and minority physician recruitment has lagged for decades[viii].

There are two factors, however, that loom above all others—economics and federalism. More on these below.

The Economic Forces Driving Fragmentation

Hospitals and other healthcare entities face daunting fiscal challenges. They are highly vulnerable to recessions and labor shortages. Even in the best of times, they face headwinds like rising operating costs, fluctuating insurance coverages and flat revenues. According to the American Hospital Association, over half of all hospitals were expected to lose money in 2022. In some cities, large chains are driving smaller hospitals to the brink of bankruptcy. In some rural communities, especially those in non-expansion states[ix], hospitals are shutting down.

Other healthcare entities face similar financial pressures. Independent pharmacy margins have been shrinking since Medicare Part D was enacted. Mental health providers strain under the weight of burdensome regulations and reimbursement limits. Many medical students are forced by financial considerations to become highly paid specialists despite more dire need for primary care physicians. Most insurance plans make specialized procedures more lucrative than essential services like primary care and telemedicine.

The Contribution of Federalism to Fragmentation

By granting so much healthcare autonomy to states, American federalism sets the table for politicizing the healthcare issue. When state politicians can win by resisting federal aid, they balkanize healthcare policies, fragment healthcare resources and turn their backs on health outcomes. In the healthcare arena, federalism is a recipe not for reflective experimentation, but rather reckless obstruction.

The US Supreme Court narrowly upheld the ACA mandate but prevented the federal government from withholding Medicaid funds from non-expansion states[x]. Despite national programs, federalism gives states sufficient autonomy to maintain vastly different healthcare regimes, and shocking healthcare disparities. Poor states—like many Southern states—often have the worst healthcare access. The uninsured rates for the 12 Medicaid non-expansion states are twice that of the 38 Medicaid expansion states. The state-run Medicaid programs adopt distinctive eligibility and coverage rules[xi].

Recent Developments

The Covid-19 pandemic killed over one million Americans, and revealed the inadequacies of our healthcare structure. Our hospitals and other healthcare facilities, neither designed nor deployed for extended crises, impeded our response. Our tribalized politicians sent competing messages to their constituencies about public health policies that should have unifed us.

The pandemic often seemed fueled by the system’s patchwork organization. Hospital beds were overrun, and finances strained. Many healthcare workers were driven from the profession. Rural healthcare providers were left reeling. States experienced drastically different outcomes—vaccination rates, intensive care unit occupancy rates, and excess pandemic-related deaths.

What did we learn? For one thing, we learned that a fragmented healthcare system—like the American system—is too disorganized to meet the challenge of a global pandemic. And, the large healthcare chains—the entities increasingly dominating US healthcare—lack sufficient financial incentives to invest in pandemic preparedness. They cannot reasonably be expected to invest in spare beds, build a reliable global supply chain, or amass adequate equipment reserves, at least, not on their own.

The US healthcare system is undergoing changes that will no doubt impact the way its resources are organized. Hospital and pharmacy mergers. Physician practice acquisitions. Primary care shortages. Staffing turnover. Financial stress, especially with rural providers. Disappointing health outcomes, especially in mental health. The ramifications are hard to predict, but such changes may afford us a generational opportunity to rebuild the US healthcare system. We should seize it.

The Impact on Healthcare Access

US ranks last among its peer nations in overall healthcare access[xii]. As Pew Charitable Trusts has reported, this is more likely a function of geography (and insurance) than medical need. In the US, healthcare access depends a lot on where one lives. As many as one-third of US citizens have been estimated to live in a healthcare desert county (a county with inadequate healthcare access). While access is usually thought of as a rural problem, many inner-city areas also have access issues[xiii].

Healthcare access can vary for different kinds of facilities and services. Emergency care—more specifically, proximity to a trauma center—is one important marker. Other markers include proximity to a primary care clinic, low-cost health center, hospital or pharmacy. Over eight million Americans are estimated to live in counties with limited access to at least four of these resources.

Rural communities suffer the worst access. In its 2020 report, Confronting Rural America’s Health Care Crisis, the Bipartisan Policy Center noted that rural areas have far fewer healthcare providers per capita than urban areas[xiv]. The ratio of primary care physicians to residents is up to six times higher in urban areas than rural areas. Millions of rural Americans live more than a one-hour drive from a hospital with trauma care services.

Closing Comments

National statistics can obscure the deadly impact of badly organized healthcare resources. The impact, however, is all too visible at the community level. Every time a hospital or clinic closes, every time a doctor takes a job with a large modern hospital system, our rural communities and inner-city neighborhoods are slammed.

Economic disruption and job losses. Inflated healthcare costs. Spotty primary care. Untreated disorders (including addiction and serious mental illness). Worsening chronic conditions. Diminished patient care and safety. Compromised care quality. Jails as mental health facilities[xv]. Wider health disparities—economic and racial. Shorter life expectancies. Estranged workers and patients.

Nationally, the byzantine distribution of healthcare resources is incredibly inefficient. Our healthcare spending is wildly uneven. From one state to the next, health insurance costs vary by as much as 150 percent. From one locale to the next, Medicare spending varies by as much as 100 percent and service costs by as much as 300 percent. These inefficiencies increase America’s overall healthcare costs.

And, as long as we continue to concentrate our healthcare resources where the profits are—instead of where the needs are—we will continue to produce mediocre health outcomes at an exorbitant cost.