America’s Healthcare System – Part 6

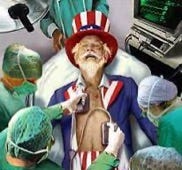

Is the US Healthcare System Really the Best We Can Do?

This is the sixth essay in Civic Way’s series on the US healthcare sector. In this essay, we start outlining healthcare’s major flaws. The topic of this essay is our nation’s disheartening health outcomes. The author, Bob Melville, is the founder of Civic Way, a nonprofit dedicated to good government, and a management consultant with over 45 years of experience improving public agencies.

Highlights:

The US has some of the world’s best medical centers, and has made great advances in areas such as mammograph screening, flu vaccines, and stroke, cardiac and cancer treatments

Despite spending far more, the US lags behind other developed countries on most vital health outcome metrics, such as life expectancy, preventable deaths and maternity and infant mortality

There are many reasons for our poor metrics—demographics, pollution, lifestyles, road fatalities, guns and overdoses—but obesity may be the most evident

Unlike the US, nations with the best health outcomes, like Australia and Netherlands, offer universal health coverage, community-based primary care and comprehensive social services

Introduction

Considering America’s scandalous healthcare bill, we don’t get the health outcomes we should—not by a long shot. We spend twice as much on healthcare as do other wealthy nations (as a percent of gross domestic product). Yet, we have some of the most anemic outcomes in the developed world.

There are many explanations for this unhappy state of affairs. The neglect of public health (and disease prevention). Erratic healthcare access and quality. Federalism. Poorly deployed and coordinated resources. A counterproductive, unsustainable financing (insurance) scheme that detaches us from our own care. Misdirected innovation. Inefficient—even archaic—administrative practices.

In this essay, we highlight some of America’s key healthcare metrics, those that showcase our strengths and others that reveal our weaknesses. We compare the US to other developed nations. And we set the stage for a closer look at our healthcare sector’s most serious flaws, and some ideas for fixing those flaws.

Macro Health Outcome Ratings

The Commonwealth Fund compares the healthcare systems of 11 high-income nations[i]. It evaluates 71 measures across five categories: outcomes, care access, care process, equity administrative and efficiency. The top-ranked nations, like Australia and Netherlands, offer universal health coverage, community-based primary care and comprehensive social services. The lowest-ranked nation, the US, does not.

The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) also tracks healthcare indicators for different nations. Even before the pandemic, the OECD found that US health outcomes compared poorly to those of other developed countries. For instance, it found that other developed nations, despite spending so much less than the US, increased their average life expectancy about six years more than the US since 1970.

The sad reality is that the US stumbles over the most fundamental health outcome markers. The lowest life expectancy. The highest preventable death rates. The worst maternity and infant mortality rates.

Where America Excels

There is some good news. Some elements of the US healthcare sector are exceptional. Many of our medical centers and hospital systems are world class, if not global leaders.

The Mayo Clinic, Cleveland Clinic, Massachusetts General Hospital, Johns Hopkins Hospital, and UCLA Ronald Reagan Medical Center, among many others, are modern marvels. The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Stanford Health Care-Stanford Hospital, and Barnes-Jewish Hospital—and many others—have outstanding reputations in their respective medical fields.

In the aggregate, the US leads other wealthy nations—or at least surpasses the peer averages—in some important treatment outcomes. The 30-day mortality rate for heart attacks and strokes. The 30-day post-hospital admission mortality rates for heart attacks and hemorrhagic strokes. The 30-day mortality rates for ischemic strokes. Such indicators are a reflection of high-quality care.

The US outperforms the peer average in cancer care. According to a Yale study published in the JAMA Health Forum, the US has a slightly better cancer mortality rate than the average rate for 22 high-income countries. However, the US spends twice as much on cancer care than the peer average. The US ranks high in care process, second in the world to New Zealand. For instance, the US has high mammography screening and flu vaccination rates compared to other developed nations.

Life and Death Indicators

There are many ways to measure health, but mortality metrics tell the story as well as any. And there are several ways to track life and death and compare US rates to those of its peer nations.[ii]

Life expectancy may be the most useful indicator for gauging a nation’s overall health. It synthesizes several factors and conditions into one measure, forecasting longevity based on current data trends.

According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, the US’ life expectancy is lower than that of its peers. Worse, the gap between the US and its peer nations has been widening. From 1980 to 2020, the US’ life expectancy rose from 74.5 years to 77.3 years. During the same period, the peer average rose from 73.7 years to 82.1 years.

During the pandemic, the US-peer gap only worsened. The pandemic brought our largest two-year life expectancy decline in decades. Peer nations also experienced a decline, but a much smoother one than the US. Ironically, given the pitched immigration debate, this gap would have been even worse but for immigration (from 2007 to 2017, immigration accounted for half of the US’ life-expectancy gains).

Other mortality indicators tell a similar story about US health outcomes.

Preventable mortality[iii] – the US has the worst preventable mortality rate among its peers

All-cause mortality rate[iv] – from 1980 to 2020, the all-cause mortality rate for the US fell 19 percent, far lower than the peer average of 43 percent (i.e., the US-world gap widened)

Premature death rate[v] – the US’ premature death rate (collective years of life lost) is worse than the peer average; from to 1995 to 2022, the rate fell 24 percent for the US and 42 percent for the peer average

Disease burden[vi] – since 2000, this rate, which combines premature deaths and disability years, has declined for the US and its peers, but the US rate is 37 percent higher than the peer nation average

The bottom line? Regardless of the indicator, the US fares poorly compared to its peers.

Maternity and Infant Indicators

It doesn’t get any better for the US when it comes to pregnancy-related health outcomes.

The US has the highest maternal mortality rate among developed countries. In 2020, the US had 23.8 maternal deaths per every 100,000 births. [Shockingly, the US rate was twice as high for Black women.] In sharp contrast, the peer average was only 4.5 deaths. The best rates were those of Netherlands (1.2) and Australia (2.02). Worse, the US-world gap for maternal mortality rates is widening.

The US also has the highest infant mortality rate among its global peers. There are several likely causal factors. Pregnancy-related chronic illnesses like diabetes and high blood pressure. Suicide and drug overdoses. Medical complications during childbirth (the US has higher obstetric trauma rates during vaginal delivery especially when instruments are used). According to the CDC, at least three-fourths of infant deaths are preventable.

This is where the US Supreme Court’s decision to overrule Roe v. Wade has tangible (and potentially tragic) implications. Abortion restrictions pose serious threats to postpartum health. More unwanted pregnancies carried to term. An even more mortifying maternal death rate, especially in states that ban all abortions.

The Search for Explanations

There is a long list of likely determinants for the US’ mediocre health metrics. Demographic diversity (worse outcomes for minorities). Pollution. Unhealthy dietary and sedentary habits. The prevalence of Type 2 diabetes and congestive heart failure, and underlying conditions like high blood pressure and cholesterol levels.

At the top of the list is obesity. There are valid concerns about mean-spirited fat shaming, but we cannot deny that obesity threatens our health, and materially contributes to our crushing healthcare costs.

Obesity[vii] is truly an American epidemic. At 40 percent, the US’ adult obesity rate is twice the average European rate and eight times the Japanese and South Korean rates. The US rate for marginalized groups is even worse. And, despite decades of warnings, the US’ obesity rate continues to climb. From 1980 to 2008, for example, the US obesity rate doubled among adults and tripled among children and adolescents. The US’ severe[viii] obesity rate has increased even faster.

Why does this matter? Obesity aggravates the underlying conditions for many diseases—high blood pressure, high cholesterol, Type 2 diabetes and sleep apnea. And obesity greatly increases the odds of contracting many maladies—coronary heart disease, stroke, cancer, gallbladder disease, osteoarthritis, even mental illness. Obesity accounts for one-fifth of all US deaths among adults aged 40 to 85.

Obesity is also a serious financial drain on our economy and public sector budgets. In 2020, obesity accounted for nearly $250 billion in national healthcare costs (about six percent of total costs). On an individual basis, obese adults incur higher healthcare costs (even higher for elderly obese adults).

Of course, there are other factors contributing to our woeful mortality rates. A higher road accident death rate. More guns and gun violence. The highest suicide rate among wealthy nations. More drug overdose deaths (especially during the pandemic). And, due to the politicization of public health, lower Covid-19 vaccination and booster rates, and higher Covid-19 death rates.

Conclusion

It is hard to compare national healthcare metrics and systems. It is even harder to pinpoint the relative impact of each causal factor on overall health outcomes. What we do know is that the US’ healthcare system does not do enough to address these factors.

The Healthcare Quality and Access (HAQ) index[ix], a composite measure of healthcare access and quality, tells us how much the US healthcare system fails its people. Compared to our peer nations, the US ranks last, well below the peer average, and way below top-ranked nations like Australia, Netherlands and Sweden.

We can do better. Given our spending and affluence, we should have the best outcomes, not the worst. If we want good health, as individuals and as a nation, we must make big changes.